|

|

|

|

|||

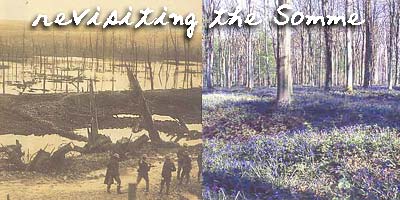

The Somme battlefield in the Ancre Valley, 1916, and today. All photos courtesy of James Power and Somme Battlefield Tours Ltd

Revisiting The Somme By Martin Stott 11/08/2002 (sound: waves and seagulls) I'm standing on the beach at Dover, about to set sail for Northern France. This seemed like a normal assignment until a few days ago, when I got a shock talking to my Dad. I'm beginning to trace my family history; he's never told us much in the past, but then he revealed that my own great grandfather died in World War I. Suddenly, this journey is becoming much more personal. Around 90 years ago, my great Grandfather must have made this same voyage. I'm traveling with a group called Kingshead Adventures, led by amateur historian Jerry Whitehead and the energetic 60-year-old John Pressdee. John's remarkable; he has walked the whole length of the First World War battlefields. And once landed, he's keen to get us out of the jeeps and into our boots as quickly as possible. John: "This would have been the walk that the British soldiers would have taken on that fateful morning of first of July, 1916, when 100,000 British soldiers on an 18-mile stretch of line got out of their trenches and walked shoulder to shoulder with 60-pound packs on their backs at regulation 2 miles an hour. Nearly 60,000 of the 100,000 became casualties, probably within the first couple of hours."It's not difficult walking the muddy fields to imagine row upon row of men in khaki slowly marching through the early morning mist to their deaths. The enormous scale of the fighting is brought home to us when we stop at the corner of a field in front of a cluster of enormous empty shells, dug up only recently. John: "The wonder is, why doesn't a shell of that weight sink? Why does it come to the surface? The movement of the substructure just pushes the stuff up, and there's something like 90 tons a year of these rusty old shells that come to the surface. And I think, the estimate is that it'll take 800 years to get rid of this lot. When these trenches were originally created, they would have been 8 feet high. Chalk straight up and down; sandbags on the side of that, sometimes supports, barbed wire even on the top of that."Amazingly, some of the original trenches still remain. These at Beaumont Hammell were home to the Newfoundland regiment. The place is now a museum. We stand facing east across the flat field. Only a few hundred feet and the tall stump of a charred tree lie between us and what were the German trenches.

Guide: "By the time the Newfoundland Regiment crossed the barbed wire here, every officer is killed or wounded; there's nobody to give further orders. So, what the men decide to do is group 'round the danger tree, as it's the only thing that is different in this field. They grouped around that area trying to figure out what to do. Do they return back to their own lines, or keep on going? Because there were such a large number of men around that one position, they became an easy target for the German machine gun positions."I'm disappointed that there's nothing to commemorate the German dead at this battle; I'm surprised to learn later that Germany lost more troops than any other nation in World War I, including Russia. And, most of them must have been ordinary working men like my great-grandfather. Everywhere we go in this area are small, neatly kept cemeteries. Jerry takes us to several. Those who live here can't escape the horror of what happened in these fields. Jerry: "Prior to any large battle, they had digging parties, digging graves before men went into battle. So, it's quite likely that men marching up the lines were passing their own graves."I'm now standing within the Thiepval memorial, which is the huge Edward Lutyens building which commemorates the names of 74,000 people who died on the Somme, whose bodies were never recovered. I'm standing now looking at names from the Manchester Regiment, which is where the Stotts came from. Manchester in northwest England, and there is on there an A. Stott. That could well be Abraham Stott -- that could be my grandfather, and I just don't know. Museum narrator: "The Somme campaign continued for 141 days. Over one million men were listed as casualties. The front had continued, but more importantly the German army had lost many troops."We visit several memorials and museums. We meet other groups doing the same thing. I'm here on a special weekend: the anniversary of the first day of the battle of the Somme. Army veterans and descendants of the dead have gathered here specially. We all meet together in the pouring rain at 7.30 in the morning, the time the battle started at the rim of a giant muddy crater on what was the German front line. (sound: whistles, gun shots and bagpipes)We sing hymns, hear poems and memorials, and then at the end, throw poppies into the crater below. One of the speakers says these men died for our freedom. I can't help wondering whether my great-granddad was really that sacrificial, or whether he was forced into this -- a victim rather than a hero, or maybe he was both. I don't know where the body of my great grandfather lies -- I will try to find out -- but I cast out a small prayer to his soul, wherever it is. I say how sorry I am that he did die, and I feel the tears welling up. It suddenly dawns on me that his death has shaped my life today. I always knew my grandfather was a violent alcoholic, but now I wonder, was it a result of losing his father in the trenches, here? His alcoholism emotionally damaged my Dad and inevitably, of course, the sensitive, scarred man he is in some way shaped me too. I can't stand here and remember my great-grandfather -- I don't know who he was. But as the sound of the pipes swirls round me, the rain soaks through my clothes, and the wind bites, I'm glad I'm here to pay my respects. From the Somme, in France, I'm Martin Stott for The Savvy Traveler.

|

|

Search

Savvy Traveler

|

|