|

|

|

|

|||

|

Easter

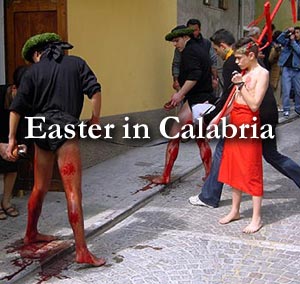

in Calabria By Frank Browning, 4/12/2002 Blood washes blood, the southern Italians say. Blood binds brothers. Blood buries enemies. Blood settles feuds. I went to Calabria, the bleak, beautiful arch of the Italian boot, to see and touch the blood of sacred sacrifice.

The train from Naples south to the tip of the boot snakes along the entire Tyrhennin coast of Calabria, a relentless necklace of bridges and tunnels beside occasional plots of onions and beans, struggling orange and olive groves, and thousands of cheap, block and stucco vacation condos. But drive inland 5 miles, up corkscrew roads and you leap backward in time, two, three, 10 centuries into small villages perched on jagged promontories of tufa and volcanic rock.

It begins on Good Friday, at night. The air is chilly. The doors to the church of the annunciation open. A group of town fathers lift up an enormous terra cotta pieta. The Madonna and the dead Jesus draped across her knees weigh several hundred pounds. The men, wearing white robes, start the slow procession, carrying her through the streets on wooden rails. The band begins a funeral dirge.

It is a collective lament, not only for the death of Jesus, but for the death of every mother's son and the continuous suffering that has been the Calabrian lot for longer than anyone can remember. As the funeral procession creeps through the tiny streets, the battiente begin to appear, one by one. They stop at houses, cafés, shops and churches to beat themselves. At each site, their wounds are washed with a combination of wine and rosemary water, which seems to stop the bleeding. A bare-chested adolescent boy carrying a red cross runs with each battiente, tied to him by a long cord. The boy is called the Ecce Homo, and represents the risen Christ who tells his disciples, "Ecce Homo -- Am I not a man?" Footprints of blood mark every stair, every passageway. Bloody handprints mark every doorway where a battiente has stopped. The next morning, the townspeople begin to tell me about one particular, devout battiente. He came from Argentina. Some say he's been coming for 20, maybe 30 years. Some say he once had cancer and recovered, and came to offer thanks to the Madonna. Others say, no, no, it was his young son who had the cancer. At noon on Saturday, he appears at the village square. His name is Gabriele, and he was born in the village of a good family. He had already bloodied himself, washed his wounds and put on street clothes. Yes, he says, he comes every year.

But why? He comes over here every year to see the Madonna because she is a really special Madonna. And when you hit yourself, do you feel pain?

And the cancer people spoke about? "No." "Nor a sick child." "No." He is married, yes, but no children. But Firenzo, who translates, says:

Silvano, speaking through his visiting American cousin, talks about the spiritual peace that settles over him as he strikes his body with broken glass.

To look at these men's legs and feet drenched in crimson blood and wine streaming down the steps of the Church of St. John the Baptist, "happy" may not be the feeling that comes to mind. But then pain is complex. The exquisite pain of childbirth, a friend reminds me, can also deliver the mother into transcendent calm. Neurologists say such transient pain causes the body to release dopamine and other neurotransmitters that parallel the ecstatic peace of opiates. To the people of Nocera Tirinese, including Silvano and even Gabriele, the Argentine battiente who happens to be a doctor, these are the reductions of a scientific mind that knows neither suffering nor passion. What matters, is the great coming home of Easter when far-flung families return to each other, when joy overcomes the memory of pain, and where the streets themselves reverberate with the story of a thousand years of survival. From time to time, both the police and the church have tried to block the procession of the Madonna and the blood ritual that accompanies it. In World War II, the government filled the town with police on one Good Friday night, but the next morning double the number of people showed up. In 1956, the church hierarchy forbade the procession. "Barbaric! Uncivilized! Superstitious!" Monsignor Vescovo Saba declared, suggesting there was something dark and pagan about all the bloodletting. Antonia Stella, now in her 80s, remembers that Saturday morning all too well.

"We want our Madonna! We want our Madonna! Let our Madonna go!" Within moments, the brotherhood who shoulder the Madonna through the streets broke the chain, forced the doors of the church open, and bore the grieving Madonna and her dead Jesus into the streets while the priests stood silently watching. And, indeed, on this weekend the priest, while present in his robes, stands well apart from the bleeding battiente -- more than 70 of them this year -- who paint the streets with their blood. As in most funerals in Catholic countries, this ancient procession is both a dirge and a celebration. Many houses set out plates of homemade soprasota sausage and cheese, as well as sweet ricotta tarts, crumbly cookies and local wine. This year, more than ever, we the media had arrived, clicking our cameras, rolling our video tapes, filling our notepads on this "medieval" rite -- never mind the vastly greater blood-letting in progress the other side of the Mediterranean, or the ritual blood cleansing 2 years earlier in Kosovo. Blood washes blood, Italians say, and for a moment, under the southern sun, it seemed to turn mourning into sweet remembrance. I'm

Frank Browning in Nocera Tirenese.

|

|

Search

Savvy Traveler

|

|